cynical regarding the research community but its all one eyed winks and back scratching regarding there

analysis. So enough with all that amd enjoy the report

Behavioural psychology applies to central bankers, regulators and politicians as much as it

does to investors. In promising to ‘fiscally retrench tomorrow’, finance ministers are exhibiting

the behavioural phenomenon of overconfidence in their future self-control. The bitter fiscal

medicine required to stabilise debt levels won’t become more palatable today relative to

tomorrow until the bond market makes it so. It can only do this through higher yields. Thus,

Ireland and perhaps now Greece lead the way. For the Japanese it’s too late.

•Why should behavioural psychology be seen as something applying only to investors?

"Behavioural" finance is a well defined sub-discipline in its own right. But where is

"behavioural" politics, !behavioural" central banking, or !behavioural" regulation? Remember

the Fed policy statements around the end of the 1990s? The ones that kept referring to the

"technology-enhanced’ rate of GDP growth? Wasn"t this herding around a bad idea the very

same herding then fuelling the NASDAQ bubble?

•And as the housing bubble inflated, Bernanke in a quite staggering display of logical

sloppiness, concluded that the risk of a housing collapse in the future was small because there

had never been one in the past # Weren"t they then guilty of !framing" their analysis in a way

guaranteed to preclude an uncomfortable conclusion? If you don"t expect to see something,

you"re less likely to see it. Similarly cringe worthy logic was used when sub-prime rolled over,

and Bernanke concluded that there was no risk of contagion to the rest of the economy

because ....er....there had been no contagion to the rest of the economy yet.... wasn"t this

textbook !recency bias" whereby the importance of recent events is over-weighted?

! It probably was, and it probably demonstrates that central bankers are as prone to be as

systematically silly as the rest of us. Indeed, just last year a study by yet more of Bernanke"s

!best and brightest" concluded that “monetary policy was not a primary factor in the housing

bubble”. I don"t want to pretend I"m any kind of behavioural expert, but isn"t this the well

documented !attribution bias" by which people attribute positive outcomes to themselves,

but negative ones to others?

•So here we are today, with regulators rounding on investment banks, hedge funds and

tax havens, apparently in denial of the reality that the problem was not the regulations but

the regulators. After all, heavily regulated institutions like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were

at the epicentre of the crisis (as was AIG, whose financial services business model was the

facilitation of $regulatory arbitrage% around Basle capital requirements). Not that it makes

any difference. The regulators are merely bowing to pressure applied by politicians whose

understanding today is as flawed as Gordon Brown"s was in the Mansion House back then.

If this sounds like a rant then I apologise & it isn"t meant to be one. We"re all fallible and

policy making is an impossible job. But that means policy mistakes are inevitable, and

I believe we"re seeing one right now.

Oscar Wilde said he could resist anything but temptation. But doing something you know you

shouldn"t is easier if you can convince yourself that this will be the last time you indulge, that

you won"t do it again. So we convince ourselves that since we"ll be strong in the future, we

can still indulge today. Whether it"s smoking, eating too much or going to the pub instead of

the gym, we delude ourselves into thinking that we will take the more difficult path next time.

A few years ago, two economists actually looked at the issue using gym membership data.1

They found that in a club in which non-members could pay a no-strings fee of $10 per visit,

people preferred to pay the $70 per month for unlimited access. And since members only

attended 4.3 times a month on average, they ended up paying an average $17 per visit. The

authors concluded this to be clear evidence of $overconfidence about future self control.%

Investors understand the affliction all too well: a stock trades at £10 and we tell ourselves that

we"re buyers at £8. But how many of us buy when it gets to £8? Some of us do, but most of

us don"t. Most of us (I can"t be the only one!) convince ourselves that it"s going lower still: “I’ll

buy at £7” becomes “I’ll buy at £6” and by the time it"s back at £8 we"re “waiting for a

pullback” Each investor has their own way of circumventing this problem. But at root, such

poor decision-making is a consequence of our fundamental underestimation today of the

discipline and even courage we will require in the future.

Last weekend, the G7 !committed" itself to the path of further stimulus. As politicians are wont

to do, they presented it as though it was somehow a difficult decision: "the position for most

countries is to support the economies now, and get the budget deficit down as the economy

recovers." said the UK"s Chancellor, Alistair Darling, nodding earnestly. Am I the only one who heard a

heroin addict steadfastly committing to his next fix?!

Well, it got me thinking about how much governments need to retrench to stabilise existing

debt to GDP levels. And although I consider myself fortunate enough to have forgotten most

of the economics I learned at university, one lesson which was useful, or in any case has stuck

with me, is of the arithmetic behind government debt sustainability.

There are lots of books containing lots of equations outlining lots of limits and theorems about

the dynamics of government debt sustainability, but the basic intuition is that if I"m a finance

minister mulling out how much money I should be borrowing, I want my GDP growth (and

therefore my tax revenue growth) to pay the coupons on any debt I take on today. If the GDP

growth rate equals that interest rate, the incremental revenue flowing into my coffers thanks to

the incrementally higher level of GDP covers my coupon payments. I don"t need to borrow any

more money and my debt ratios are stable. But if the interest rate is higher than GDP growth, my

incremental tax revenue won"t cover interest payments. I"ll be in deficit and I"ll have to issue

more debt to plug the gap and my debt ratio will rise. The only way I can prevent further debt

growth is by running a primary budget surplus (i.e. a surplus excluding interest payments).

There are nuances and qualifications to this arithmetic, and limitations too, but in essence the

fault line between sustainable and unsustainable debt dynamics can be summarised as:

maintaining a stable debt to GDP ratio requires governments to run a primary balance

proportionate to the difference between interest rates and GDP growth.

Before seeing how our governments compare, two qualifications are necessary. Firstly, the

European estimates are distorted by the recent !convergence" within the eurozone which

allowed periphery economies temporarily higher GDP growth rates and lower interest rates.

This makes on-balance sheet debt loads appear more stable for those economies than they

actually are. Secondly, the calculations show only those surpluses required to stabilise the

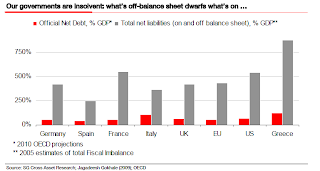

debt loads which are on-balance sheet. And it"s important to be clear about this. According to

Gokhale3, most government indebtedness is in the form of unfunded pension and health

liabilities, which are unrecorded and effectively off-balance sheet (see chart below). I"ll come

back to these shortly.

But sticking with the on-balance sheet debt for now, the calculations shown in the following

chart (over the page) use the equation in the footnote at the bottom of page 2 and give a

decent first stab of who needs to do what.

The countries on the right are in the fortunate position of paying a rate of interest which is

below their GDP growth rate. Provided interest rates don"t change from these (historically very

low) levels, they can run deficits without increasing on-balance sheet debt. The US, the UK

and Switzerland both currently fall into that category. Japan doesn"t. With bond yields at

around 1.5%, !trend" nominal GDP slightly negative, and on-balance sheet debt to GDP at

around 200%, it should be aiming for a primary surplus of 3.3% in order to stabilise its ratio.

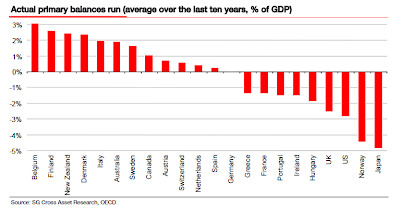

Now look at the next chart which shows the primary balances governments have actually

Now look at the next chart which shows the primary balances governments have actuallyachieved. I was surprised to find Belgium and Italy running such aggressive primary surpluses,

but this is consistent with the broadly stable debt ratios those countries have seen recently.

The US, the UK and Japan especially have been running pronounced primary deficits.

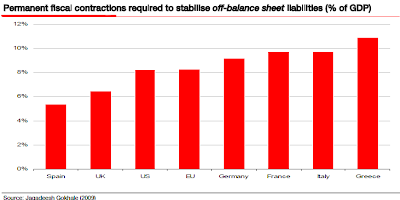

If we add both charts together we can compare the primary balances governments should be

If we add both charts together we can compare the primary balances governments should berunning with those which they"re actually running, to get a better feel for the difficulty

governments are going to have to face up to in order to merely stabilise their on-balance sheet

debt ratios. The next chart does this. Those on the left have been running budget balances

consistent with falling on-balance sheet debt to GDP ratios, while those on the right haven"t.

The US, the UK, Greece, Portugal and Norway (?) all fall into this latter category.

Eyeballing this chart, one might think governments !only" need a 3% underlying contraction of

fiscal policy in order to right the ship. Wouldn"t doing that over a number of years be

plausible? Perhaps, but I can"t find any examples of it having happened before. And while that

doesn"t make it impossible it does illustrate both the political difficulty of following such a

path, and the behavioural biases present in politicians" confidence that they will--if it is difficult to summon the

political courage today, why will it be easier tomorrow?

But consider this: all countries, and especially those to the right in the chart, are enjoying

But consider this: all countries, and especially those to the right in the chart, are enjoyingexceptionally favourable financing positions, with government bond yields near unprecedented

lows. Should anything push bond yields higher, even by just a percentage point, the onbalance sheet debt

situation will become explosive. This is the situation in Japan where the

8% contraction required to rein in its already explosive debt ratio is politically impossible. And

again, remember that the estimated 8% required contraction assumes the Japanese

government can continue to fund itself at a 1.4% JGB yield, which is clearly unrealistic.

If the on-balance sheet position today looks dicey for the rest of us, the off-balance sheet

numbers are far more worrying. The following chart shows Gokhale"s estimates of the

perpetuity surpluses governments would have to run to meet the current outstanding

obligations which are both on- and off-balance sheet. The chart speaks for itself. Such fiscal

deflation is clearly a political impossibility.

Apparently heroine addicts can become so drug dependent their bodies cannot withstand the

Apparently heroine addicts can become so drug dependent their bodies cannot withstand theshock of withdrawal, and failure to continue taking the drug triggers multiple organ failures.

I just wonder how apt that analogy is to our governments" debt dependency today. As long as

governments think that taking these difficult decisions to end the addiction will be easier in the

future than it is today, they will never take the decision !today." At the very least, there will

have to be a sufficiently large bond market !event" to force the issue.

HOME

No comments:

Post a Comment